For the past year, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has promoted the idea that the end of the pandemic would bring workers off the sidelines, reducing upward pressure on wages and easing the forces of inflation. That’s proved accurate until now, but Powell needs to let go of the fantasy that the trend has a lot more room to run.

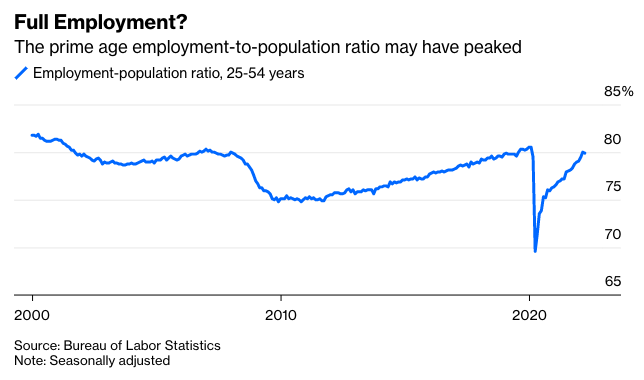

As Friday’s employment report showed, U.S. adults just aren’t returning to the job market in large numbers anymore. In a sign that things can’t get much better, the employment-to-population ratio in the U.S. fell in April for the first time since April 2020 despite a hiring market with nearly two jobs posted for every unemployed person. The ratio retreated to 60% from 60.1% a month earlier, including declines among workers ages 25 to 54, who are thought to be in the “prime” of their working lives.

Even before Friday’s numbers, the notion that a pool of untapped labor could somehow resolve the U.S.’s massive labor supply-demand imbalance was increasingly looking like wishful thinking. As of March, 80% of prime working-age individuals were employed in the U.S., just below the pre-pandemic peak of 80.5% and above the 77.5% average for the 10 years before the pandemic. It fell to 79.9% last month, but how much better could it get?

The workers-on-the-sidelines thesis had increasingly come to rely upon the return of older workers, including the members of the baby-boom generation, who had good reason to go into retirement with a deadly virus circulating and their investment accounts surging in value. Maybe endemic Covid-19 and the backpedaling stock and bond markets will prompt a rethinking of those decisions, but it’s hard to see that in the numbers — nor should anyone bank on such a development having a significant impact.

Yet Powell is still talking about returning workers as a source of optimism. In his view, there are simply too many job openings for the number of available workers, driving up wages. The employment cost index — a broad gauge of wages and benefits that gives the clearest picture of labor costs — rose by the most on record in the first quarter. Friday’s report showed that average hourly earnings rose 0.3% in April from March, less than economists had expected. (But that number, unlike the ECI, is susceptible to changes in the mix of jobs in the labor market. As Renaissance Macro Research pointed out, a drop in retail trade earnings probably compressed the overall number.)

In Powell’s perfect world, Fed interest-rate policy would prompt companies to reduce the number of job openings (demand); more workers would materialize (supply); and he would be able to orchestrate a “softish landing” for the economy, as he put it Wednesday:

We think through our policies, through further healing in the labor market, higher rates, for example of vacancy filling and things like that, and more people coming back in, we’d like to think that supply and demand will come back into balance. And that, therefore, wage inflation will moderate to still high levels of wage increases, but ones that are more consistent with 2% inflation.

That’s a remarkably tough needle to thread, and Powell’s going to need a lot of luck to carry it off.

If there was a silver lining in Friday’s labor numbers, the Black employment-population ratio — one of the most depressed since the pandemic — recovered to 58.6% from 58.3%. Clearly, that’s still showing room for improvement and holds out some hope for labor market supply.

But the central bank shouldn’t rely on a significant bump in additional labor force participation to tamp down the pace of wage increases and prevent a wage-price spiral. It’s essentially a prayer, and it shouldn’t form the base of any policy framework. The Fed faces an extraordinarily difficult path to raising interest rates without pushing up unemployment and tipping the economy into recession, and it may be time to stop pretending otherwise.

Source: Bloomberg